Google Cloud Dataset Storage Options

In one of my projects, we exclusively relied on Google Cloud Platform (GCP) for training our video generative model. We used GCP’s TPUs for training and had to store our dataset on GCP as well. Our dataset consisted of videos with a total size of 6.5T. There are two data storage options GPS provides: persistent disks and storage buckets. We’ve tried them both, and below I will present our findings for the most cost-effective option.

Persistent Disks

At the beginning of our project, we trained our models on v4 TPUs and stored our data on Standard Persistent Disk. The good thing about persistent disks is that they only charge for the allocated size and not for reading the data. The Standard Persistent Disk was priced $0.04 / 1 gibibyte per month, so our 6.5T dataset cost us ~$8.54 per day, which was pretty acceptable. However, as our compute demand grew and couldn’t be met with just v4 TPUs, we expanded to other TPUs series, such as v5p and v6e. We found that Standard Persistent Disk wasn’t supported with them. The cheapest disk option v5p supports is Balanced Persistent Disk, which is priced at $0.10 / 1 gibibyte per month, bringing our dataset cost to ~$21.35. The lowest-tier disk option v6e TPU supports is Hyperdisk ML, costing ~$60 for our dataset. However, the biggest cost issue with these two disk types is that, unlike Standard Persistent Disk, they don’t support attaching more than one TPU pod with more than 64 cores. So not only would we have to manage three disk types for each TPU series, but we would also have to replicate any Balanced Persistent or Hyperdisk ML disks if we are running multiple v5p or v6e pods. To make it more concrete, let’s say we have 6 runs running in parallel: 1 on v4, 3 on v5p, and 2 on v6e. It would cost us ~$192.59 per day. This potential cost increase led us to explore the other GCP storage option: Google Cloud Storage (GCS) buckets.

GCS

GCS, unlike persistent disks, charges for stored size and read operations. For our 6.5T dataset, the storage part was $4.3 per day, and the read part was $3.1 per TPU pod. So, in the same example of six parallel runs above, it would cost us $22.9, which is much better.

Storing the dataset on GCS provides two additional benefits. The first one is the ease of data maintenance. Persistent Disks can only be attached in read-only mode to a multi-host TPU pod, so whenever we needed to update the data, we had to detach them from the training pod, attach them to a temporary single-host TPU, perform the update, detach, and attach them to the multi-host TPU again. Second, GCS buckets are per region, for example, us-east5, meaning TPUs in any zone in this region can read from it. Persistent Disks, on the other hand, are per zone, for example, us-east5-a, so if a TPU is in the same region but in a different zone, say us-east5-b, it won’t be able to attach the disk.

Our first attempt to read the dataset from the GCS bucket was by attaching it as a filesystem using gcsfuse. It allows using the standard Python filesystem API, and we could reuse our dataloader code with no changes.

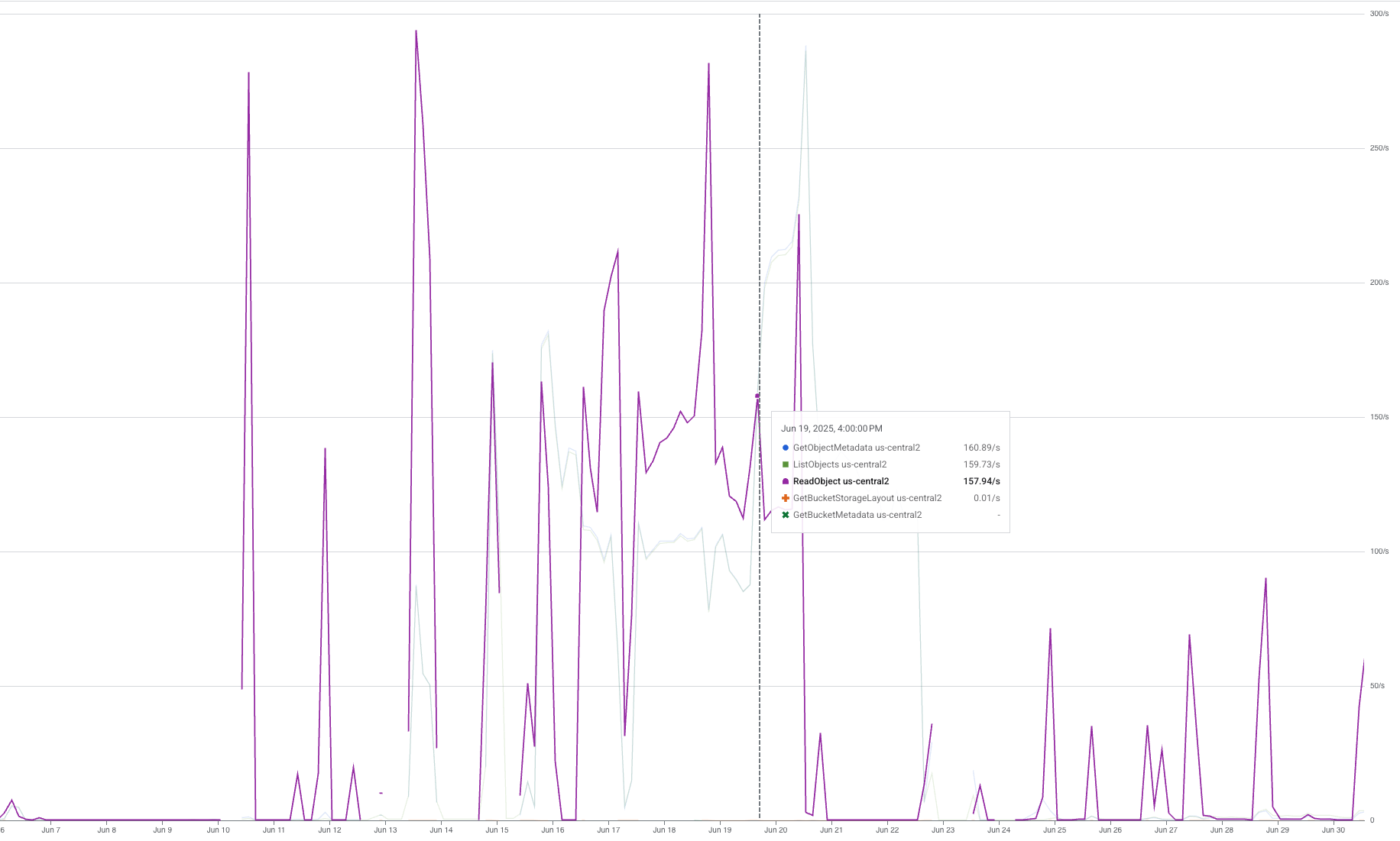

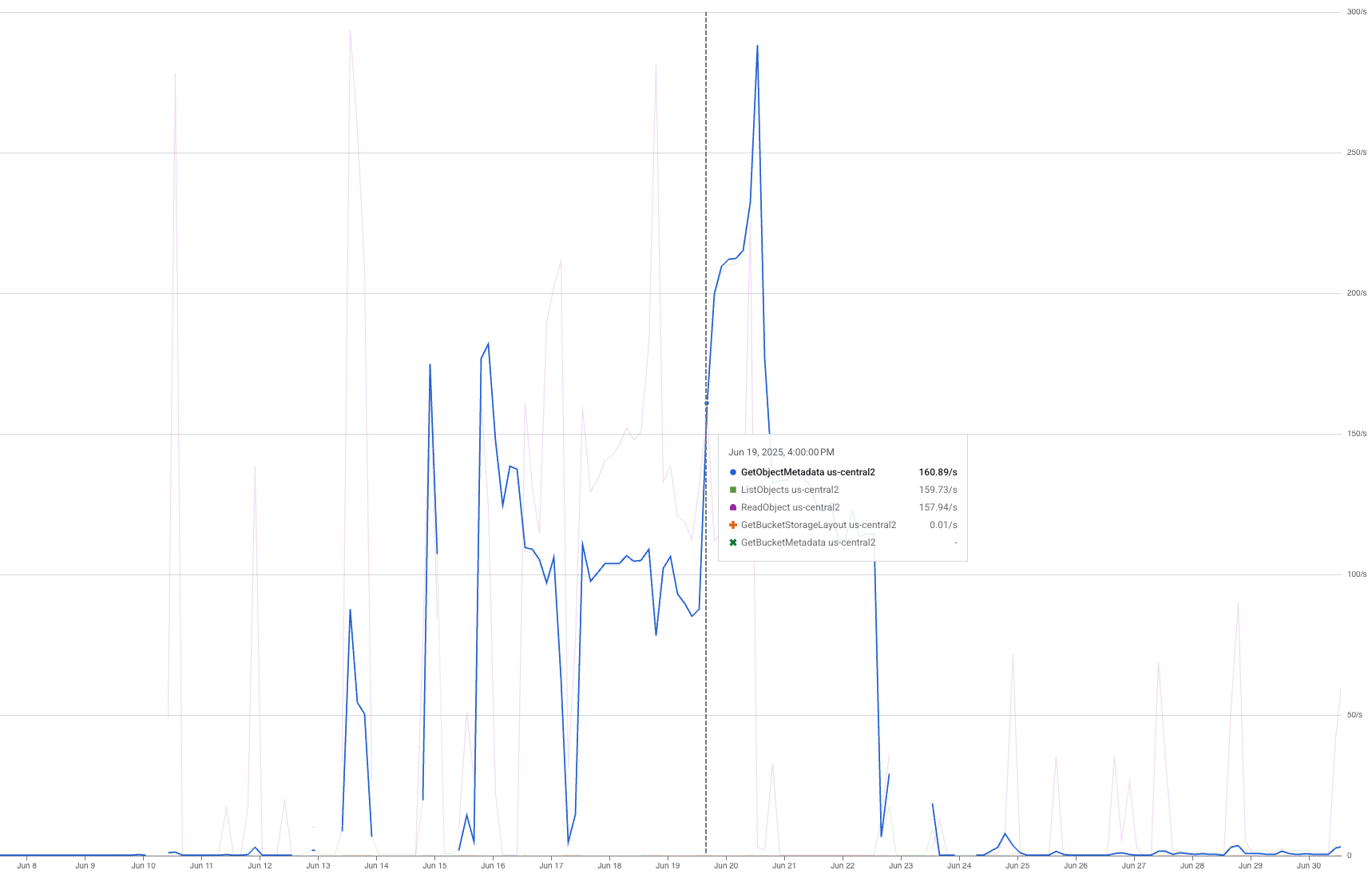

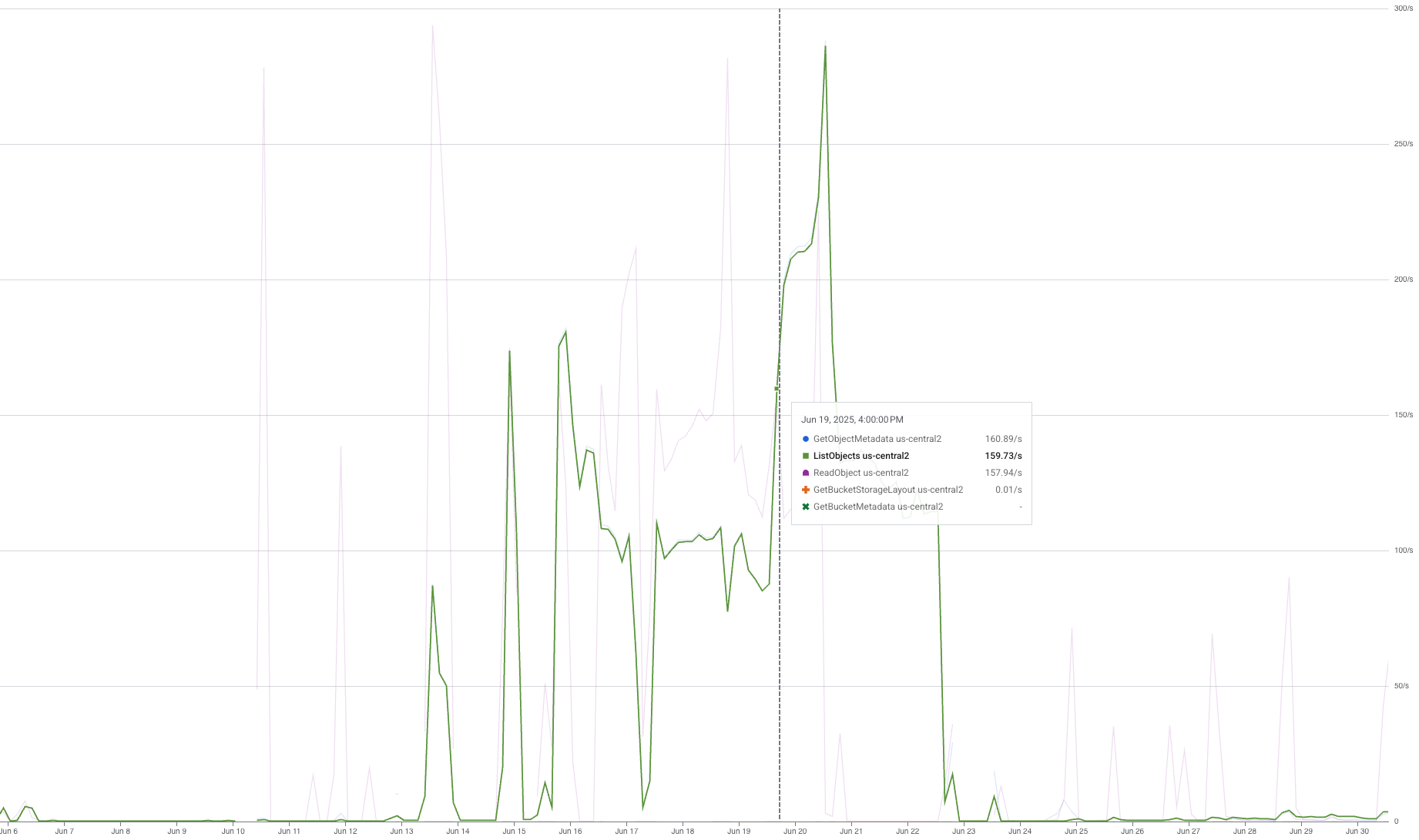

When we did a trial run using a single TPU pod, we got a $6.2 increase in “Regional Standard Class B Operations” and a spike of $38.75 in “Regional Standard Class A Operations”. Digging deeper into our usage graphs, we identified three spikes in ReadObject, GetObjectMetadata, and ListObjects requests:

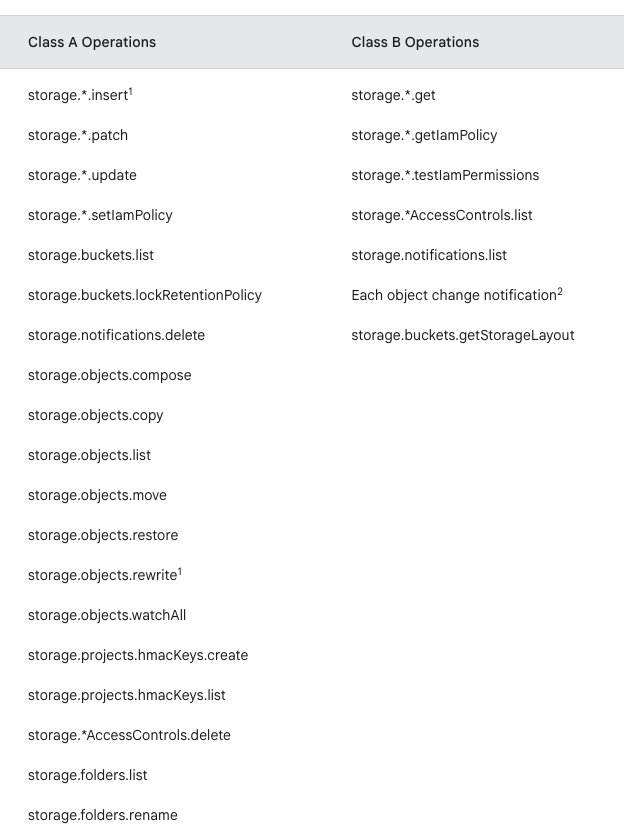

ReadObject was expected, but the other two were not. According to this table in the GCS doc:

ReadObject is class B, GetObjectMetadata is also class B, explaining the double cost of “Regional Standard Class B Operations” from what we estimated, and ListObjects is Class A. Class A operations are primarily write operations and cost x12.5 more than Class B, resulting in the significant $38.75 in “Regional Standard Class A Operations”.

It turned out that the gcsfuse filesystem is implemented so that it queries the directory list and file metadata every time a file read request is issued. These weren’t needed for our dataloader’s functionality, so we set out to find a better solution.

Next, we tried implementing a custom dataloader using gcsfs, a Python library that provides a file-system-like interface to GCS. Although it stopped sending the ListObjects requests, it still sent unnecessary GetObjectMetadata requests, doubling our Class B operation cost.

Finally, we implemented our dataloader using the Google Cloud Storage library, which provides a dedicated API for interacting with the storage service. We manually download the file from the bucket to a local temporary file using:

1

2

bucket.blob(object_name)

blob.download_to_filename(local_path)

And the rest of our dataloader stays the same.

This approach yielded the expected $3.1 per day in Class B operations, with no Class A operations costs.

Conclusion

GCS bucket storage has proved to be the most cost-effective option for training on GCP with large datasets. The storage part of the cost is much cheaper than that of persistent disks and doesn’t grow as you scale your compute. The reading operations part does grow with the compute scale, but, given the correct implementation via the native google-cloud-storage, stays pretty low, and can be further optimized with batched downloading techniques like webdataset.